The Physical Impossibility of Extinction in the Mind of Someone Living

When there's a shark in the water, don't you swim like hell for the shore?

What do you call a dead shark in a box?

In 1997 a female great white wound up biting its way into tuna nets off the coast of South Australia. There it began menacing the scuba divers who manage the vast holding pens in which immature tuna are farmed. At the time the world’s most feared shark wasn't a protected species in Australia, so after a short debate the fishermen decided the simplest solution was to kill it. The next most obvious thing after that was to sell it. A few museums expressed interest in the corpse.

After a short interlude during which its stomach was searched for the remains of a missing woman, the shark eventually passed into the ownership of Wildlife Wonderland, a theme park devoted to giant earthworms, located ninety minutes outside of Melbourne. The nature of the imagined connection between subterranean invertebrates and aquatic predators is promising territory for speculation, but there isn’t space to do it justice here. Maybe it's simply the idea of inhuman things weaving below us in the dark. After all, while we think of them attacking at the surface, sharks spend much of their time in the mesopelagic zone - also known as the twilight zone - where there's insufficient light for photosynthesis to occur.

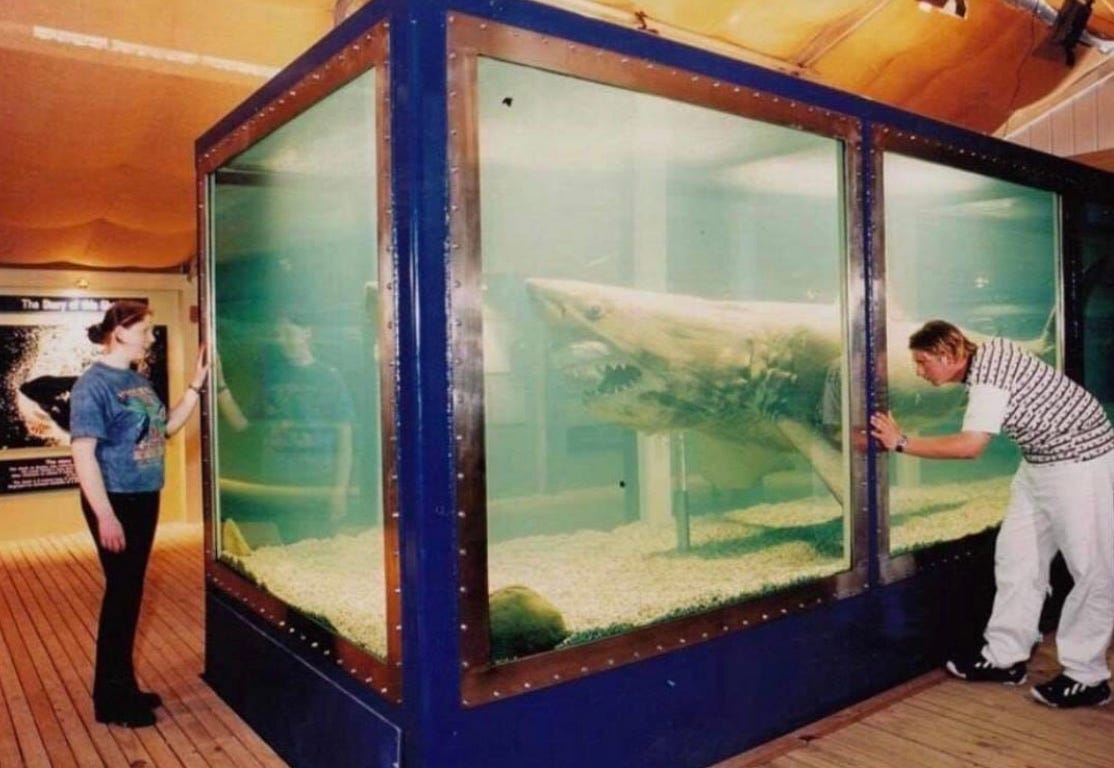

At Wildlife Wonderland the shark was placed inside a metal and glass tank filled with formaldehyde. For around fifteen years, it enjoyed an uncomplicated afterlife. Hundreds of thousands of visitors a year came to stare down her curled lip and bared jaws. A few presumably stayed on to explore the habitat of the Gippsland worm.

There’s no great mystery to our fascination with sharks. They are saw-toothed, doll-eyed avatars of calamity. Always hunting, always hidden - we were smart enough to fear them long before Benchley and Spielberg got involved. People pay small fortunes to spend half an hour submerged in a steel cage while great whites high on bloody chum swim lazy circles around them. In the last few years at least three different films have been released with the same basic narrative: fun-loving tourists go cage-diving, sharks gather, carnage ensues. It’s a classic story - hubris, nemesis, Carcharodon carcharias.

But what about preserved sharks? Well, it's always good to know your enemy. Even better if your enemy is constrained by death, glass and stainless steel. But dead or alive, our instinct isn't to look away. We can picture ourselves on the menu. The hollow clang of an anchored buoy, twilight silvering the waves, arms pulsing gently at the surface. Then a sharp downward tug. Agony. Skin and muscle in ribbons. A bright plume of blood dissipating into the unanimity of water. It would be bad luck, with the chances of being killed by a shark believed to be around 300 million to 1 - far less likely than death by lightning. But so much easier to imagine.

The struggle of man versus beast is timeless. When it's all of us against all of them, the sharks and bears and lions and crocodiles don't stand a chance, poor things. But one on one, the beasts do pretty well. A shark is an existential threat, but on a scale our brains can comprehend. When we look at them, when we pose in natural history museums with our heads between the reconstructed jaws of great whites and megalodons, we’re imagining that fate, glad that it isn’t ours, but at least content that the size of the danger matches the severity of the ending. But beyond a certain scale our imaginations falter, undermining our ability to believe in eternal fates and big ideas. This is a serious limitation, perhaps even more so than a shark’s need for constant motion.

For a while the Australian great white’s fate seemed neatly contained. At some point in its journey from coastal waters to crime lab to custom-made vitrine, it was christened Rosie. Nobody remembers why. Then in 2012, Wildlife Wonderland was shut down, reportedly because it lacked the right permits to display live animals. For six years the park succumbed to the region's atavistic climate, its buildings falling into various sun-blistered states of disrepair, the one dead animal on display all but forgotten.

Memento Mori

Beneath Rosie’s main tank at Wildlife Wonderland was a second hidden container made of concrete. Its purpose was to catch the toxic preserving fluid in case of leaks. In this respect, embalmed sharks have something in common with the doomed firefighters of Chernobyl, whose coffins were placed on concrete slabs to prevent radiation seeping into the Moscow groundwater. We honor the dead, but remain understandably wary of their tendency to try and take us with them.

We also do our best to honor dead places. With most of the classical world uncovered centuries ago by wealthy white men in pith helmets, modern explorers have turned their attention to the recently abandoned. Urban exploration is an internet phenomenon, powered by digital photography and cheap broadband. It seeks to bring back to our regulated civic environment some of the danger and excitement of encountering the unknown.

Monuments to contemporary arrogance, weakness and folly are often tantalizingly close at hand. Abandoned hotels and holiday resorts on the edge of town, their pools green with algal rain, rusting sunloungers tangled like the bones of ancient quadrupeds. Closer still the crumbling relics of defunct trades, their demise often already several industrial revolutions deep. At first, urban explorers posted long written narratives explaining how they evaded security and found their way around, punctuated by photographs of graffiti tags, precipitous drops and jagged metal. Then mobile video came along and they didn’t have to write so much.

Chernobyl was the location of the first urban exploration story to go viral. In 2004, a woman using the handle “kidofspeed” posted a blog with photos of her riding a motorbike through the exclusion zone surrounding the reactor. Even without social media amplification, the story spread across the nascent web. Like a post-Soviet Marianne Faithfull, kidofspeed rejected convention from the saddle of her bike. She reclaimed part of her ruined homeland, if only for a short while counted off by the tick of a Geiger counter. People loved the idea: the buildings were still empty, the concrete sarcophagus was crumbling, but the pictures showed nature making an unexpected comeback. Except it turned out not to be true. The photos of the abandoned town and plant were taken from a tour van with permission to enter the zone, the biker jacket and helmet props brought along to create the illusion of solo exploration.

But one aspect of the story wasn’t fake. Somehow, nature really had found a way to survive Chernobyl’s unprecedented dose of poison. But with everything from fallen pine needles to Pripyat’s pariah dogs still emitting radiation, it isn’t so much a case of the environment making a comeback as it making the most of our absence. Before war came to Ukraine, tours of the exclusion zone were an established attraction. Background radiation is low enough that a few hours carries less risk than a medical x-ray, though you still wouldn’t want to eat anything grown in the zone’s soil.

In 2018, Rosie was rediscovered by a genuine urban explorer. He uploaded footage of her to YouTube, sparking a mold rush of people wanting to see her now-neon tank sitting abandoned among all the worm cast-offs. Within only a few months, the lid had been wrenched off. Dangerous fumes leaked out. Someone threw a chair into the tank, someone else tried to smash the glass. Luckily for them it was solidly made, with several layers of reinforced laminate. They only managed to break the outermost pane. If they'd succeeded, they would have found themselves bathing in five thousand gallons of carcinogenic formaldehyde, over a ton of dead shark swimming towards them.

Death Denied

Damien Hirst has put a lot of sharks inside a lot of boxes. The artist’s online catalogue is currently being updated, but from a quick survey he’s pickled at least ten, ranging from the tiddlers preserved in the likes of Swimming Form in Endless Motion (1993) to a 6.8m-long basking shark encased in Leviathan (2006-2013).

Hirst’s first shark sculpture is possibly the most recognizable work of art created in the past half century. A 14ft tiger shark suspended in pristine blue-ish formaldehyde, encased in a segmented tank of glass and painted steel. When it was shown at the Saatchi Gallery in 1992, it seemed to perfectly represent the dangerousness of so-called “Young British Art”. In the minds of critics and casual observers, that danger had to do with irreverence, self-promotion and eye-watering prices; with hindsight it would’ve been wiser to worry about standing near 23 tons of steel, toxic fluid and dead flesh pieced together by an art-school graduate rather than an engineer.

Like Rosie, the tiger shark began to decay over time. According to an interview with Hirst in the New York Times, it rotted from the inside out, turning its tank cloudy (Rosie’s tank was equipped with a mechanical filter to keep it clean, but it stopped working after the park was closed down). In 1993, curators at the Saatchi flayed the shark and mounted the hide over a fiberglass frame, clarifying the preserving fluid with bleach. Hirst had envisioned his sculpture as something terrifying - big enough and solid enough to seem capable of eating the viewer. Reduced to just its skin, it became weightless. He said you could tell it wasn’t real.

In 2004 the sculpture was sold to an American hedge fund manager who paid Hirst to replace the taxidermy with another tiger shark, properly preserved this time. The new artwork was caught swimming beneath the Ship of Theseus somewhere off the Queensland coast. For a cost well over six figures, the corpse was taken back to the UK in a purpose-built freezer, where a specialist from the Natural History Museum used hundreds of needles to inject formaldehyde deep into its tissue and cartilage. This time, it would remain pristine for centuries. After a few years on loan to the Met and a quick trip back to London, shark Mark II now sits in a private collection somewhere in Connecticut.

The conceptual method behind Hirst’s shark sculpture and its many siblings is confrontation. Almost all of the pieces have names alluding to mortality or the afterlife. When you encounter them, you are standing in a gallery (or possibly the home of a billionaire), which - James Bond movies aside - are the last places you’d expect to come face to face with a fish that could kill you. Earlier this year, one of Hirst’s smallest and least-celebrated shark tanks sold for almost $2m; the larger ones easily reach eight figures on the rare occasions when they change hands. Curators and preservationists with advanced degrees look after them, making sure the captives are always swimming straight at us through clean glass. The message is clear: death is coming.

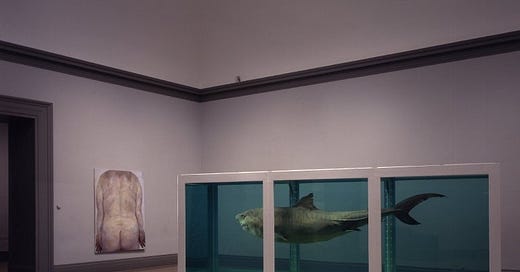

In 1997, the same year that Rosie was caught, Hirst finally got his hands on a great white. Rather than the sectional, reinforced style of his earlier vitrines, The Immortal (1997-2005) uses uninterrupted spans of glass. Compared to Rosie’s tank, it is a sleek, almost sporty piece of engineering, and the shark within is posed mid-lash, as if propelling itself towards a kill. According to a cached copy of Hirst’s site, it has only been exhibited once before, at a solo show in Qatar.

While most of them belong to respected public and private collections, one of Hirst's sharks is the centerpiece of a casino bar in Las Vegas. As culture his work still has currency; in a rising art market it pretty much is currency. In contrast, Rosie’s purpose was meant to be educational, even if like Saatchi’s 1997 Britart exhibition, the owners of Wildlife Wonderland probably also had sensation on their minds. But what about after her rediscovery?

At first the plan was destruction, on the grounds that the tank was a danger to the public. With the lid off, fumes filled the room. Urban explorers experienced headaches within seconds of entering the building. Some who still wanted footage apparently wore respirators. But as word of Rosie’s impending doom spread, a campaign was launched to save her. Eventually the owner of another museum (this time dedicated to crystals and fossils) stepped in and paid around half a million dollars to transport the tank to his property.

At her new home the formaldehyde was drained and replaced with glycerol, a non-toxic alternative. Rather than a serene float, Rosie now sits at the bottom alongside her chair. The new owners decided to leave the tank as they found it, complete with graffiti and a shattered outer pane. It’s a memorial to what happens when we forget what we are supposed to have learned. But even if they wanted to spruce up the exhibit, not much could be done to reverse the damage to Rosie herself. Nearly a decade of neglect has left her with brown, wrinkled skin and permanently receding gums. Rather than an apex predator frozen in mid-bite, she looks like angry jerky.

Object Permanence

Human babies typically develop object permanence before their first birthday. It’s a simple concept - our model of the world becomes sophisticated enough that we understand things don’t cease to exist simply because we no longer sense them. From this basic starting point comes foresight, planning, responsibility and the urge to be remembered after we are gone.

Object permanence has also been observed to lesser degrees in animals. Crows develop it at a similar rate to human children, while dogs and cats are both able to solve simple puzzles about the location of hidden objects. For a time, fish were thought to be too cognitively limited for this kind of mental modeling. But recent experiments suggest otherwise, with several species - including sharks - exhibiting the ability to keep a goal in mind even when subject to a scientist-enforced “detour”. For both predators and prey it is presumably useful to remember that their counterparts persist even when they are out of sight.

But unlike birds and dogs and fish, human object permanence has a broad spectrum. Beyond a certain point, we don’t just know that our parents are still there when we close or cover our eyes - we know that France remains too, as does Warren Buffet and what's left of the polar ice caps. More than that, we know that we remain. Depending on our mood, we can feel like the subject or object of our own lives - but whichever it is, we know we are permanent.

Hirst called his dead shark in a box The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living (1991). The title teases us for our inability to comprehend the material consequence of mortality. Oh, you can’t imagine dying, it seems to say, well how about now? Whether a genuine reconciliation with the idea of death is achieved by most observers is impossible to say. But based on how we are handling a larger, less artistically constrained threat, it seems unlikely.

For a species mostly terrified by death and obsessed with self-preservation, our inability to address, let alone prevent, the climate crisis is an ever-deepening mystery. Conspiracy theorists lay the blame on a plutocrat-owned media and a satrapal political class. But that explanation is inadequate. The scale of danger posed by newspapers no one reads and politicians no one listens to is far too small for an ending as severe as extinction. After all, if you know there’s a shark in the water, don’t you swim like hell for the shore?

From the very beginning, art, abetted by religion, has tried to find ways to make us confront mortality. To see and believe and feel that there really is an end coming, whether we like it or not. But what we are left with are creepy ossuaries, haunted stories and embalmed sharks that make people gasp with wonder rather than understanding. Science tells us that the world is becoming inhospitable; hurricanes and floods and soaring temperatures show us that it’s true. We are only a couple of degrees away from staple crop yields falling by half and sea levels rising to a point where half a billion people are displaced. But aside from a handful of activists, there’s no uprising for survival.

Rather than selfishness or apathy or self-deception, a flaw this big demands an explanation of equal size. At the punchline of a well-known joke about obliviousness, two fish who apparently take their environment for granted ask each other “what the hell is water?” (their species isn’t stated, so we can pretend they’re sharks). What if, like those fish, we simply take our world for granted? What if we’re incapable of imagining a planet that can’t support our continued existence? Rosie the great white and Damien Hirst’s many nameless sharks ask us to consider our frailty, our place in the food chain, the responsibility we bear. But for the most part all we see is a scary animal in a box.

And if we can’t believe in the possibility of our own death, how can we ever believe that everything else will die?